Climate Change Trapping Heat in Water Beneath Antarctic Ice Shelf; May Also Be Key to Another Scientific Mystery

ByIn a new study, scientists have suggested climate change is preventing heat toward the bottom of the ocean from escaping from under the Antarctic ice shelf.

According to CTV News, researchers at McGill University now say the rare phenomenon known as the Weddell polynya to have shut down the body of water for about 40 years. Scientists discovered the body of water under the Antarctic ice shelf in the late 1970s.

"The fact that we can still have a surprise like this after studying the climate system for decades shows just how complex and dangerous (climate change) is," study co-author Eric Galbraith told CTV News.

In their study, published in the journal Nature Climate Change, the McGill team paired up with scientists from UPenn to analyze tens of thousands of samples taken by ships and floating robots. The samples and measurements have been extracted over a period of at least 60 years and the results indicate the water has become less and less salty since the 1950s.

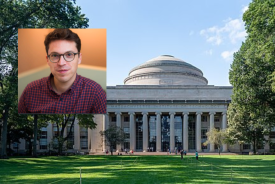

"Deep ocean waters only mix directly to the surface in a few small regions of the global ocean, so this has effectively shut one of the main conduits for deep ocean heat to escape," study lead author Casimir de Lavergne, a recent graduate of McGill's Master's program in Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences, said in a press release.

With this study, scientists may also be able to explain why the deepest layer of the ocean's water, the Antarctic Bottom Water, has gradually grown smaller over the past few decades.

"This agrees with the observations, and fits with a well-accepted principle that a warming planet will see dryer regions become dryer and wetter regions become wetter," study co-author Jaime Palter, a professor in McGill's Department of Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences, said in the release. "True to form, the polar Southern Ocean - as a wet place - has indeed become wetter. And in response to the surface ocean freshening, the polynyas simulated by the models also disappeared."

© 2025 University Herald, All rights reserved. Do not reproduce without permission.