Researchers studying six adults who had one of their brain hemispheres removed during childhood to reduce epileptic seizures found that the remaining half of the brain formed unusually strong connections between different functional brain networks, which potentially help the body to function as if the brain were intact. The case study, which investigates brain function in these individuals with hemispherectomy, appears November 19 in the journal Cell Reports.

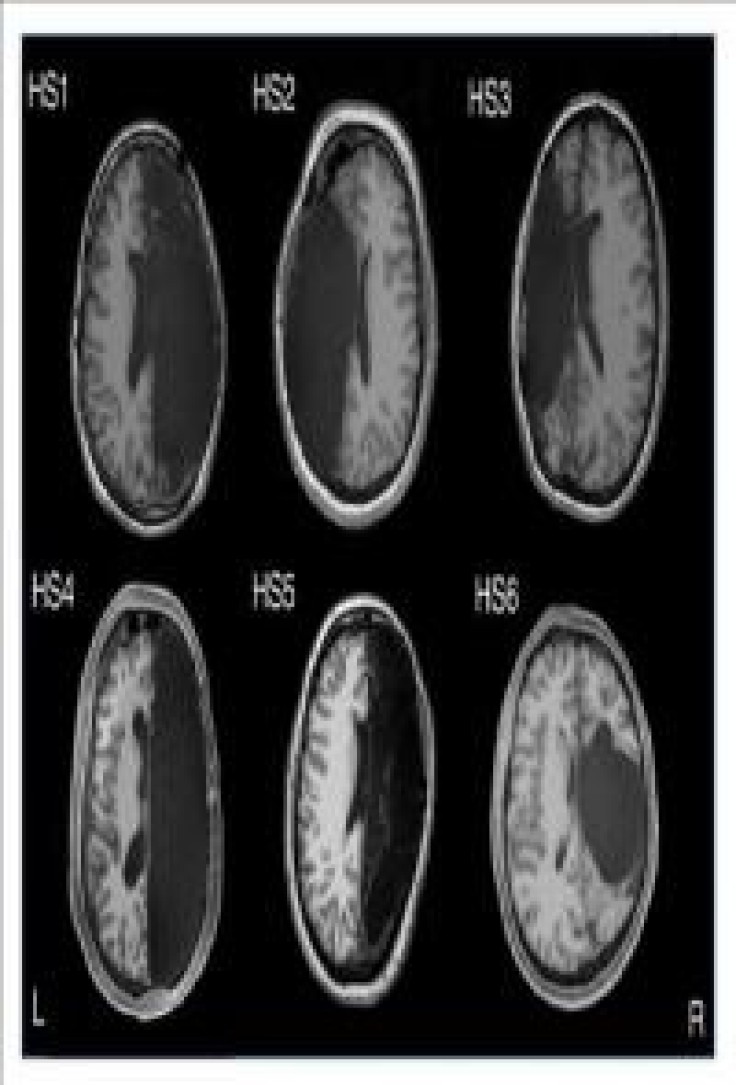

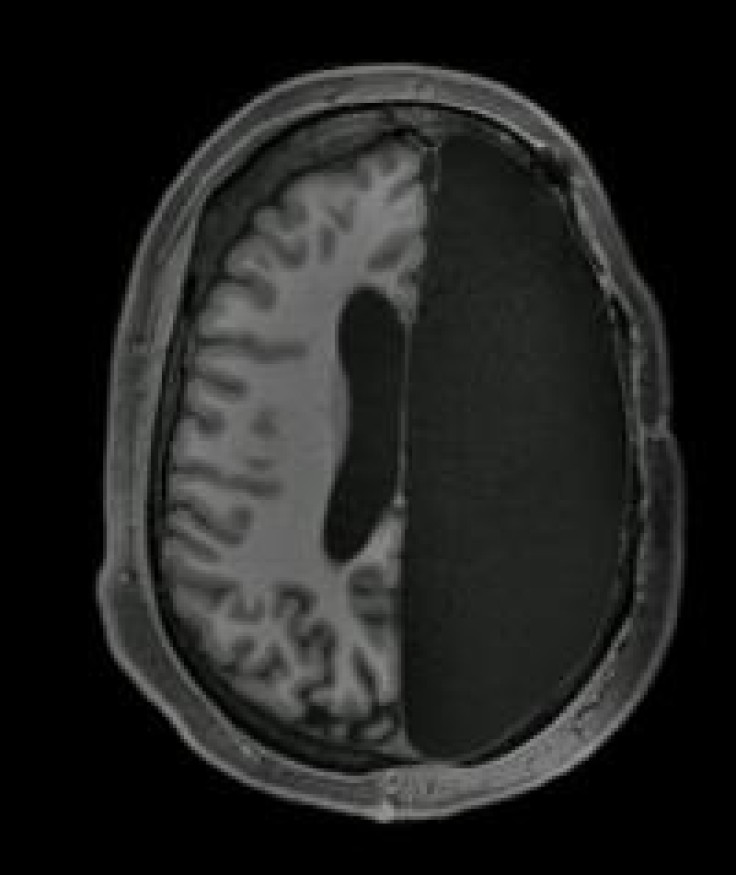

"The people with hemispherectomies that we studied were remarkably high functioning. They have intact language skills; when I put them in the scanner we made small talk, just like the hundreds of other individuals I have scanned," says first author Dorit Kliemann, a post-doc at the California Institute of Technology. "You can almost forget their condition when you meet them for the first time. When I sit in front of the computer and see these MRI images showing only half a brain, I still marvel that the images are coming from the same human being who I just saw talking and walking and who has chosen to devote his or her time to research."

Study participants, including six adults with childhood hemispherectomy and six controls, were instructed to lay down in an fMRI machine, relax, and try not to fall asleep while the researchers tracked spontaneous brain activity at rest. The researchers looked at networks of brain regions known to control things like vision, movement, emotion, and cognition. They also compared the data collected at the Caltech Brain Imaging Center against a database of about 1,500 typical brains from the Brain Genomics Superstruct Project.

They thought they might find weaker connections within particular networks in the people with only one hemisphere, since many of those networks usually involve both hemispheres of the brain in people with typical brains. Instead, they found surprisingly normal global connectivity--and stronger connections than controls between different networks.

All six of the participants were in their 20s and early 30s during the study, but they ranged from 3 months old to 11 years old at the time of their hemispherectomies. The wide range of ages at which they had the surgeries allowed the researchers to home in on how the brain reorganizes itself when injured. "It can help us examine how brain organization is possible in very different cases of hemispherectomy patients, which will allow us to better understand general brain mechanisms," says Kliemann.

Moving forward, the hemispherectomy research program at Caltech, led by Lynn Paul (senior research scientist and principal investigator) in the laboratory of Ralph Adolphs (Bren Professor of Psychology, Neuroscience, and Biology and the director of the Caltech Brain Imaging Center) hopes to replicate and expand this study in order to better understand how the brain develops, organizes itself, and functions in individuals with a broad range of brain atypicalities.

"As remarkable as it is that there are individuals who can live with half a brain, sometimes a very small brain lesion like a stroke or a traumatic brain injury like a bicycle accident or a tumor can have devastating effects," says Kliemann. "We're trying to understand the principles of brain reorganization that can lead to compensation. Maybe down the line, that work can inform targeted intervention strategies and different outcome scenarios to help more people with brain injuries."

© 2025 University Herald, All rights reserved. Do not reproduce without permission.