If not for an actress and a pianist, there might not be a GPS and a WiFi technology today.

Hedy Lamarr was already the toast of Hollywood in the late 1930s and early 40s, renowned for her portrayals of femme fatal roles. Few of her contemporaries realized that she was also an inventor. She had previously designed streamlined aircrafts for business tycoon Howard Hughes, who was her boyfriend.

Lamarr later met an avant-garde pianist, composer and novelist, George Antheil, who also had interest in engineering. During the war, the pair learned that the enemy forces were jamming the Allied radio signals, so they both ventured into finding a solution.

The result of their study was a signal transmitting method called "frequency-hopping spread spectrum," which was patented under Lamarr. Many of today's wireless technology still use the technique.

For ground-breaking technology, it may seem as a surprising source, but Lamarr and Antheil's tale fits perfectly with an increasing understanding of the "polymathic" mind.

In addition to helping explain the specific characteristics that allow some people to effectively juggle different fields of expertise, new research shows that there are many benefits to pursuing multiple interests, including increased life satisfaction, quality of work and innovation.

The concept of "Polymath" is an unfamiliar topic which i s niw gaining traction in terms of discussion. The word has its origins in Ancient Greek and was first used at the beginning of the 17th century to mean "many learning." But there is no straightforward way to decide how advanced and how many levels those learning and disciplines must be.

Most researchers argue that in at least two seemingly unrelated domains, you need some form of formal acclaim to be a true Polymath.

Waqas Ahmed in his book The Polymath, published earlier this year, is one of the most detailed reviews of the subject.

Part of the inspiration was somewhat personal. To date, Ahmed has spanned many fields throughout his career. Ahmed has worked as a political reporter and personal trainer with an undergraduate degree in economics and postgraduate degrees in international relations and neuroscience.

Today, as the artistic director of one of the world's largest private art collections, he pursues his love of visual art while also working himself as a professional artist. Nevertheless, with all these different fields of expertise, he still does not consider himself as a polymath.

He only considered those geniuses who had made significant contributions to at least three fields, such as Leonardo da Vinci, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, and Florence Nightingale among many others.

Higher-than-average intelligence, as you might suspect, certainly helps to become one. Also often the polymaths were self-reliant and individualistic. They were happy to teach themselves and were driven by a great desire to fulfill their creativity combined with a more holistic view of the world at large.

Ahmed explained that the polymath not only moves between different spheres of knowledge and disciplines. They also seek fundamental correlations among those fields, so as to find a relevant relationship of each of these ideologies.

Like any characteristics of personality, all of these attributes will have some genetic basis, but the environment will also be a great influence. Ahmed points out that there are many different areas in which many children are interested but our schools, colleges, and then occupations tend to push us towards one or two specializations only.

So many people, if only motivated in the right way, can be polymaths. Ahmed suggests that if you are tempted to lead a more 'polymathic' life, you can use your time more efficiently to make room for multiple interests.

Wannabe polymaths can use this to their benefit by rotating their interests - ensuring that they use their brains in each field at maximum efficiency while avoiding unnecessary energy after achieving their cognitive saturation point.

When you turn to another different task, you can find that you can apply yourself better. Therefore, switching between various types of tasks will improve your overall productivity.

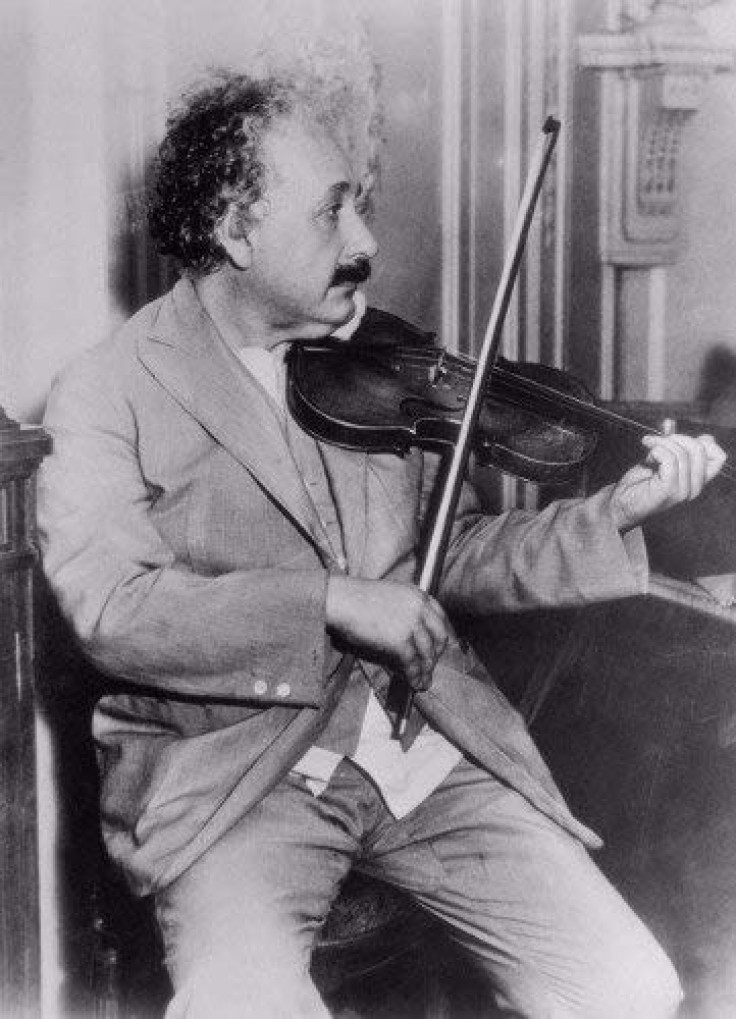

This approach was reportedly used by Albert Einstein, who was an accomplished violinist and pianist as well as a physicist. Whenever he faced an intractable problem, he would play music and then solve it later. It used his time much better than continuing to agonize fruitlessly over math or physics.

© 2025 University Herald, All rights reserved. Do not reproduce without permission.