UPenn Team Discovers Previously Unknown Egyptian Pharaoh, Woseribre Senebkay, And First Evidence Of An Unknown Dynasty

ByA University of Pennsylvania-led group discovered a previously undocumented pharaoh in the deserts of Egypt, the Daily Pennsylvanian reported. Combing the tombs of the ancient city of Abydos, the group, headed by Josef Wegner, was at first surprised to find the innards of the tomb mostly intact, which mostly included paintings. Prior to scientific discovery and documentation, most ancient tombs are raided for their valuables. Though this one showed clear evidence of plundering (the body was dismembered), the bandits must not have thought enough of the paintings to take them along (if they weren't ancient tomb raiders and had seen "American Pickers," they would have).

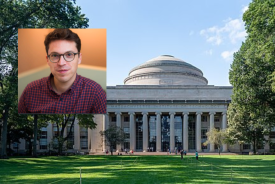

The tomb also contained the name of its occupant, Woseribre Senebkay, puzzling Wegner and his team of UPenn professors and graduate students (called "Team Dude," by Jennifer Wegner, Josef's wife and the team's only female) because it didn't match any previously known pharaohs. (Some news outlets are referring to him as "pharaoh," other as "king"; the terms are somewhat interchangeable, but also dependent on time period and other factors, according to my light research.)

"We were pretty puzzled for two days. It was a king's name that didn't appear anywhere else in history, so we didn't know who he was at first," Wegner, an associate curator in the Egyptian Section at the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, told the Daily Pennsylvanian.

Eventually, they would connect the tomb's inscriptions with an era of ancient Egypt only recently proposed by Kim Ryholt in 1997 and still not 100 percent confirmed, the Abydos Dynasty. Senebkay was identified as the period's first or second king.

"It's exciting to find not just the tomb of one previously unknown pharaoh, but the necropolis of an entire forgotten dynasty," Wegner said.

According to two other members of "Team Dude," Penn grad students Paul Verhelst and Matthew Olson, the ancient king likely died in his mid to late 40s and ruled around 1650 B.C. Around this time, central ruling broke down, leading to smaller kingdoms like Abydos, according to the Guardian.

"Not only do you have his name [on] the tomb, but you also have him there as well," Olson said.

Senebkay's tomb remained hidden so long because it was originally intended for another Pharaoh during an earlier, but better documented period, according to the release. Presumably, that convenient switch led to some inconvenient confusion among archaeologists, who probably didn't expect Egyptians, known for burying heaps of gold and food with their fallen rulers, to be so thrifty and resourceful with King Senebkay.

Of the timing of the discover, Guardian blogger Stuart Jeffries wrote:

"These are exciting times to be an Egyptologist. Earlier this month, archaeologists disclosed that everybody's favourite mummified teenage pharaoh, King Tutankhamun, had been buried with his penis at 90 degrees to make him look more like Osiris, god of the afterlife, for reasons too complicated to get into right now."

© 2025 University Herald, All rights reserved. Do not reproduce without permission.