Are endangered animals raised in captivity just not sexy enough? Can we breed sexually-desirable traits in endangered animals to proliferate at-risk species?

Those are but a few of the implications of a new study that discovered female rats looking for mates in a cutthroat environment ensure the survival of their genetic line by giving birth to males with more urinary pheromones, or chemicals designed to seduce the opposite sex. According to lead researcher Wayne Potts, females compete by making their sons more "sexy," Live Science reported.

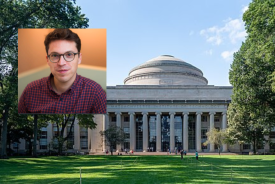

"If your sons are particularly sexy, and mate more than they would otherwise, it's helping get your genes more efficiently into the next generation," Potts, a biologist at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City, told Live Science.

Female rats are producing sexually vigorous males because of the environment (and not strictly because of genetic predispositions), leading Potts to wonder if altering the environment for endangered animals bred in captivity could spur the birth of sexier offspring, which could inspire further reproduction of the species, Live Science reported. Simply introducing more competition could be the key to the notoriously difficult work of breeding animals born and raised in captivity, according to Potts.

Potts' work adds to a growing (but poorly understood) body of research called epigenetics, or the process by which the environment affects the expression of certain genes, including how social and environmental factors experienced by parents affect the genetic outcomes of their offspring, according to The University of Utah.

"This study is one of the first to show this kind of epigenetic process working in a way that increases the mating success of sons," Potts said.

To attain their results, Potts raised mice in the typical laboratory fashion (one mate each), termed "monogamous," and in conditions meant to mimic their natural environment, termed "promiscuous," according to Live Science. Taking the offspring of both conditions, they bred all four combinations (monogamous with monogamous, monogamous with promiscuous, and so forth), and discovered sons of promiscuous mothers produced 31 percent more pheromones than sons of monogamous mothers, regardless of which condition the father was raised in. Sons of promiscuous fathers, however, produced 5 percent less pheromones than those of monogamous fathers, suggesting fathers view their sons as competition.

"If you're worried about your sons impinging on your own reproductive success, then why make them sexy?" Potts asked.

Before Potts' research can be applied to endangered animals, he'll have to account for the finding that male mice that emitted more pheromones had significantly shorter life spans than those that produced less. The production of pheromones expends a ton of energy, according to the study.

© 2025 University Herald, All rights reserved. Do not reproduce without permission.